Not only did he contribute with Marx in 1844-48 to the formation of a new worldview - the philosophy of praxis or historical materialism - but he developed an analysis and argumentation on subjects that Marx did not want to or couldn’t study. One of them is the question of primitive communism - which is not absent in Marx, especially in his unpublished “Ethnological Notebooks”, but is much more developed in Engels’ book The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State [1] (1884).

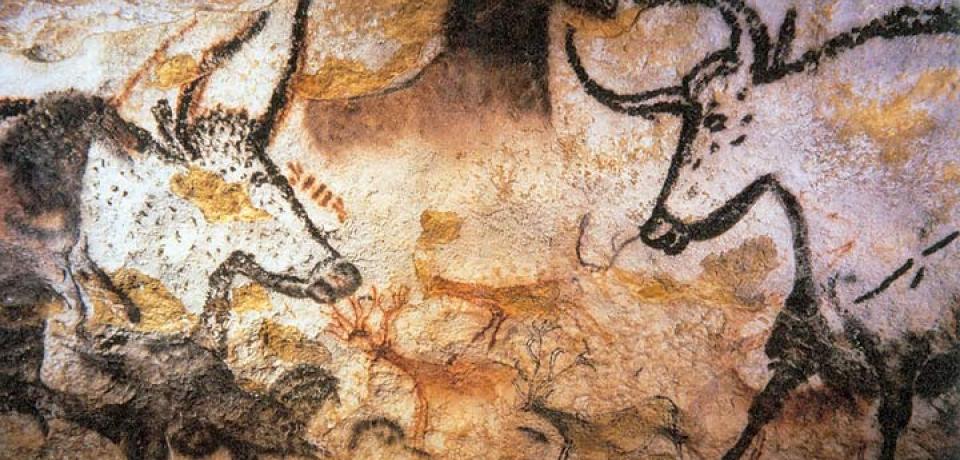

Copyright: Lascaux, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Basing himself on the work of the American anthropologist Lewis H. Morgan on prehistoric gentile societies, Engels studied, with great interest and enthusiasm, this primitive form of society without classes, private property or state. A passage from The Origin of the Family illustrates this sympathy: “And a wonderful constitution it is, this gentile constitution, in all its childlike simplicity! No soldiers, no gendarmes or police, no nobles, kings, regents, prefects, or judges, no prisons, no lawsuits - and everything takes its orderly course… All are equal and free - the women included… But it was broken by influences which from the very start appear as a degradation, a fall from the simple moral greatness of the old gentile society. The lowest interests – base greed, brutal appetites, sordid avarice, selfish robbery of the common wealth – inaugurate the new, civilized, class society.”

Engels’ analysis of early communism - another term for what anthropologists have called “gentile society” (of “people”, tribal, clan, or family community) - has several important methodological implications for the materialist conception of history:

1. It delegitimizes the attempt of bourgeois ideology to “naturalize”" social inequality, private property and the state as essential characteristics of all human societies. Primitive communism reveals that these social institutions are historical products. They did not exist for thousands of years in prehistoric times and they may cease to exist in the future.

The same is true of patriarchy. Following Morgan and other anthropologists of the time (Bachofen), Engels uses the concept of “matriarchy” to define primitive communism. It is a questionable term, which has caused much controversy among historians, anthropologists and/or theorists of feminism until today. I think the most important aspect of what Engels says in the passage we are quoting: in those primitive societies there was a high degree of equality between men and women. It is also a question here of demystifying patriarchy, self-proclaimed as a timeless structure, common to all social formations.

2. It breaks with the bourgeois vision - shared by a large part of the left - of history as linear progress, a continuous advance of “enlightenment”, civilization, freedom and/or of the productive forces. Engels proposes, in place of this conformist doctrine, a dialectical view of the historical process: in many ways, civilization represented progress, but in others, it represented a social and moral regression from primitive communism.

3. It suggests the existence, in the course of human history, of a dialectic between past and future. Modern communism is obviously not a return to the primitive past, but it takes up, in a new form, aspects of this first form of classless society: absence of private property, of state domination, of patriarchal power. .

It is important to note that in Origin of the Family Engels does not refer only to the prehistoric past. Like Morgan, he notes that even in his day there were still indigenous communities with this kind of egalitarian social organization. This is the case, for example, with the Confederacy of the Iroquois, an alliance of indigenous nations in North America for which he does not hide his admiration: primitive communism is therefore also present in the 19th century.

These ideas of Engels have been echoed by some of the best Marxist thinkers of the twentieth century. For example, Rosa Luxemburg, in her (posthumous) book “Introduction to Political Economy”, devotes almost half of her work to primitive communism. She sees the struggle to defend these communal social forms against the brutal imposition of capitalist private property as one of the reasons for the resistance of the peoples of the periphery to colonialism. According to Luxembourg, primitive communism is present on all continents; in the case of Latin America, she noted the persistence, until the 19th century, of what she called “Inca communism”. Without knowing Luxemburg’s book (he did not read German), José Carlos Mariategui, the founder of Latin American Marxism, uses the exact same term, Inca communism, to describe the indigenous communities (ayllus) at the base of Inca society before Hispanic colonization. For him, these indigenous community traditions were maintained until the 20th century and could constitute one of the main social bases - with the urban proletariat - for the development of the modern communist movement in the Andean countries.

Today, in the 21st century, faced with the ecological crisis which threatens human life on this planet, another aspect - mentioned but little studied by Engels - must be taken into account. “Primitive Communism” was a way of life in genuine harmony with nature, and today indigenous communities are characterized by a deep respect for Mother Earth. It is therefore no coincidence that they are, from the north to the south of the American continent, at the forefront of resistance to the destruction of forests and the poisoning of rivers and land by multinational oil companies, pipelines and agri-food exporters. Berta Caceres, the murdered indigenous leader in Honduras, is the symbol of this tenacious struggle, which in Brazil results in the fight of indigenous peoples to save the Amazon from the systematic destruction promoted by the kings of cattle and soybeans - with the open support of the neofascist and ecocidal government of Jair Bolsonaro.

2 December 2020

Michael Löwy

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook