A Brahmin family photograph from the 1880s, likely from Maharashtra. Image: Wikimedia Commons

The geographer Sanjoy Chakravorty recently promised that, in his new book, he would “show how the social categories of religion and caste as they are perceived in modern-day India were developed during the British colonial rule…” [1] The air of originality amused me. This notion has been in vogue in South Asian postcolonial studies for at least two decades. The highest expression of the genre, Nicholas Dirks’s Castes of Mind, was published in 2001.

I take no issue with claiming originality for warmed-over ideas: following the neoliberal mantra of “publish or perish,” we academics do it all the time. But reading Chakravorty’s essay, I was shocked at the longevity of this particular idea, that caste as we know it is an artefact of British colonialism. For any historian of pre-colonial India, the idea is absurd. Therefore, its persistence has less to do with empirical merit, than with the peculiar dynamics of the global South Asian academy.

The origins of this idea lie in Bernard Cohn’s work on the census’ role in codifying jāti, and on the role of Brahmin native informants in shaping the British imagination of Hinduism. The first process was peculiar to British colonialism, since this bureaucratic technology was new. The second process is familiar: Brahminism has shaped state ideology since the Gupta empire. Exceptions – like the 17th-century Nāyaka states that celebrated the commerce and cultural life of ‘left-hand castes’ – only prove the rule.

Somehow, scholars leapt from Cohn’s work to a thesis that caste as we recognise it is a poisoned gift of the British. In the region where I have some expertise, the Marathi-speaking pre-modern world, English and Marathi scholarship amply document caste as both material oppression and varna ideology. More viscerally, low caste sants speak to us, centuries later, of their poverty, their back-breaking labour, and the dishonour and loneliness of their social position. Consider just two examples, the first an abhaṅg by Tukaram, the second by Janabai:

Born a shudra, I was a tradesman.

God comes to me like a sacred keepsake…

I was miserable in mundane life

Ever since I was orphaned.

Famine reduced me to utter poverty, I lost all honour.

I watched my wife starve to death…

* * *

Jani has had enough of mundane life—

But how will I repay my debt?

Discard your grandeur

To grind grain with me.

Hari, become a woman

Bathing me and washing my dirty clothes.

You carry the water with pride

And gather dung with your own two hands…

For both poets, imagining God as their companions in the daily grind of labour, poverty and social marginality, poetry and devotion were their only refuge. To read them and deny the existence of caste ‘as we might recognise it today’ is a violence that no historian should commit.

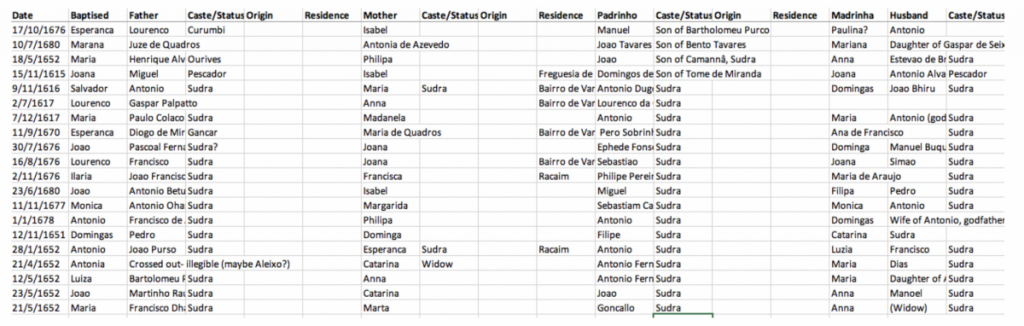

In my own research, evidence of caste as an organising principle of social life is everywhere. At the Goa State Historical Archives, I recently transcribed a late-17th-century register of slave manumissions. The vast majority of the freed slaves were from lower castes in the Konkan, such as kunbis and kolis, which still exist today:

So durable and adaptable is caste that it continued even after conversion. In the 17h-century baptismal records of the village of Loutulim, we see how caste even affected godparenthood, a new form of elective kinship brought by Catholicism.

Undoubtedly, caste changed under the British – but this is trivially true of every period of Indian history. Caste adapts to changing state technologies and political economy, but remains a total social fact, organising every realm of Indian life: legal, economic and political, religious, aesthetic and cultural.

This is not to minimise the pernicious nature of colonialism, or postcolonialism’s critique of it. The horrific immiseration of the Indian countryside by British colonialism – which wiped out rural wealth, laid waste to millions of lives in famine after famine, and destroyed artisanal economies that had driven global trade for centuries – affected the lower castes in particular. Simultaneously, British education created both the upper-caste elites who became their successors, and nurtured lower-caste thinkers like Mahatma Phule and Dr B.R. Ambedkar who articulated devastating critiques of varna ideology. Colonialism, like all forms of rule, had complex effects on caste. Yet the British did not create it.

Given how evidently untrue this thesis is, the question is why it persists. The answer, in part, is that postcolonial studies is its own echo-chamber. Works like these are not vetted by boring historians of pre-colonial India like myself. Rather, under the sexy sign of theory, postcolonial scholars make sweeping claims about pre-colonial India, without expertise in the period.

More importantly, this thesis allows upper-caste intellectuals to maintain privilege in both India and the US. The Indian educational system, which disproportionately benefits upper castes, allows them to migrate. Once there, without the prop of caste privilege, postcolonial theory provided an avenue for critiquing white elites. Scholars like us have held elite academic positions for decades now on the basis of representing the brown voice of the subaltern in the West.

By then foisting the blame on colonialism, we absolve ourself of complicity in caste, even as we continue to benefit from caste oppression in India. Academic gate-keeping – through patronage networks of teaching and hiring, journal editorial boards and conference invitations – keeps this monopoly in place. Meanwhile, the same tired theory is repackaged and resold by scholars eager to profit from this monopoly. If you think about the academy as an economic institution, it is a fascinating case of covert collusion.

I speak as an insider, a whistleblower. I come from precisely this class of upper-caste diasporic intellectuals. The big secret of South Asian postcolonial theory is that its obfuscatory language – signalling sophistication to mere mortals – actually hides power. The scholars avow progressivism, but their theories defend privilege in both India and the US.

No wonder that Hindutvadis in both countries are now quoting their works to claim that caste was never a Hindu phenomenon. As Dalits are lynched across India and upper-caste South Asian-Americans lobby to erase the history of their lower-caste compatriots from US textbooks [2], to traffic in this self-serving theory is unconscionable.

The painful irony is that Dalit scholars have said this before, while struggling to get past academic gate-keepers and scholarly chowkidars. It took a Chakravarti saying it on Twitter for this critique to garner mainstream attention. In 2019, the question is not whether the subaltern can speak – it is whether us double-Brahmins of the academy, who perform progressivism while maintaining caste, will ever allow them to be heard.

Ananya Chakravarti

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook