- Myanmar in South-East Asia –

- The colonial period

- World War II and its aftermath

- Towards the military dictators

- Resistance movements

- The particularities of the

- Instances of Buddhism

- Aung San Suu Kyi and the (...)

- Bamars and National Minorities

- The geopolitical impact

- Punishments

- The European Union and sanctio

- Our solidarity

East Asia is currently one of the epicentres of the world [1] of important movements of democratic resistance, initiated in reaction to the authoritarian and dictatorial drift of many political regimes. After Hong Kong and Thailand, Myanmar has become, in the region, the “incandescent front” among these hot fronts. It now occupies a special place because of the social scale of the civil disobedience movement triggered in reaction to the military coup of February 2021; and also because of the extreme violence with which the ruling junta is trying to drown all opposition in blood. [2]

On Thursday 1 April 2021, two months after the coup, the website Irrawaddy counted 540 victims (there are now more than 800), murdered by the forces of repression, including dozens of children and young adolescents. In 1988, an anti-dictatorial revolt with characteristics quite similar to the one we know today was broken by a bloodbath: at least 3,000 dead in a few months. Everyone in Myanmar is aware of this precedent, which haunts the survivors of the fighting generation who lived through it, the so-called “’88 generation”. It is possible that it is different today, but the battle is turning out to be arduous and prolonged, because what is at stake is the radical eviction - once and for all! – of the army from the political, administrative and economic centres of power which it has occupied continuously since 1962, from the top to the bottom of the state, from the top to the bottom of society.

Before February 1, 2021, power was shared, in a very unequal fashion, between the elected civilian government, led by the National League for Democracy (NLD), which had won hands down democratic elections and, in a dominant position, the army (called Tatmadaw). The Constitution, drafted by the latter, guaranteed it a blocking minority in all legislative assemblies (25 per cent of unelected seats - any amendment to the Constitution required at least 75 per cent of the votes), the management of key ministries (Defence, Interior and Border Security), the absence of any civilian control over the military institution - which, on the other hand, appropriates whole sections of the economy: Myanmar is one of the countries where the “khaki economy” is the most developed [3].

The coup of 1 February was therefore not intended to “conquer” power. It was a result of the impasse of a democratic transition blocked sine die by the refusal of the army to give up its prerogatives. Tatmadaw acted first, so that its grip on the state and the country would not gradually be eroded in the face of the development of civil society, the electoral legitimacy of the National League for Democracy and its leading figure, Aung San Suu Kyi who was exerting, in the corridors of power, pressure to widen the fields of competence of her government [4]. The NLD was not the only target of this “preventive coup”, the same was true of associations, unions, etc. Having learned the lessons of 1988, the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) was set up the very day after the putsch, bringing together the young “Generation Z” (high school students), health workers, civil servants who went on strike en masse, unions, including the CTUM federation…. By virtue of their place in the family, society and production, women have played a leading role in this overall movement. [5] Feminists welcome this visibility and note significant progress compared to the mobilizations of 1988, a change in gender models, “In 1988, the leaders were men. This time, they’re women. It’s exciting.” They are afraid, however, that this modification will only be temporary if the situation “normalizes” [6]

Concerning the NLD, many of whose leaders were immediately arrested, it convened formally a representation, in hiding or in exile, of the elected parliament, under the acronym of CPHR. [7]

The aim of the democratic uprising is not simply to “erase” the putsch and return to the previous situation, but to create a new situation which makes it possible to pose (and settle) a structural question: the place occupied by the army for five decades in Myanmar society. A fight that promises to be long and arduous and which requires active international solidarity.

The major turning point that has taken place recently is that armed resistance is spreading. It was the preserve of ethnic minorities on the outskirts of the country. It is now manifesting itself in the central plain. The movement continues to take massive forms, such as the refusal of educators and teachers to resume work under the orders of the junta [8], but it has also had to go underground. Tatmadaw is deployed throughout the country and does not hesitate to bomb villages in the countryside or threaten the destruction of urban neighbourhoods. In regions like Mandalay and Sagaing, in particular, military patrols are ambushed, informants in the service of the regime are liquidated, new administrators responsible for replacing dissident territorial officials are executed... The junta retaliates with measures of collective punishment (burnt villages, looted houses, stolen livestock, rapes, summary executions…).

The purpose of this article is not to take stock of the present situation and what is at stake in it, something which has been attempted elsewhere [9], but rather to focus on the context of the Myanmar crisis and its background... In doing so, we come up against the complexity of realities and legacies that it is difficult to understand when we do not have an intimate knowledge of the country (which is my case: I have travelled in the region, but not in Myanmar).

Myanmar in South-East Asia – Notes on history and geography

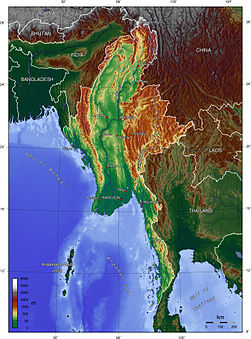

Regarding the background, it is probably useful to return to the process of the historical formation of Myanmar in its geographical and regional framework. [10] Today it has more than 56 million inhabitants for an area similar to that of France and shares its borders with Bangladesh to the west, India to the north-north-west, China to the north-north-east, Laos to the east and Thailand to the south-south-east. Its coast, in the southern part, borders the Andaman Sea and the Bay of Bengal (in the Indian Ocean).

Myanmar in Asia

South-East Asia is made up of a peninsula and a set of archipelagos stretching out to our antipodes. By its dimensions as well as by the size of its population, it is comparable to Europe, from the Atlantic to the Urals. It constitutes this “angle of Asia” which draws a line of demarcation between the countries bordering the Pacific or the Indian Ocean. We will stick here to the peninsula alone. Except for the French, who think of their former colonies, the term Indochina evokes a region where two civilizational lineages meet, those of India and China: to which have been added, with the help of trade and then colonization, those of the Arab world and the West.

This region is not a “catch-all” where could be stored “remains”, after a partition of countries between South and East Asia. It has a history of its own, but this history has produced a great deal of diversity and many contrasts, which should stop us from resorting to simplifying generalizations.

Cultural and religious influences have contributed to the diversity of South-East Asia. In pre-colonial times, it was perhaps the region of the world where civilizational influences were the most numerous. Animism is present in a diffuse way. Buddhism is a shared reference from Burma to Vietnam, including the countries of the Mekong Delta. Hinduism is pervasive from Burma to Indonesia, via Thailand and Malaysia. Beyond Vietnam, Confucianism accompanies the expansion of the Chinese diaspora. From the sixteenth century, Christianity took root in the Philippines - and before that, Islam was introduced to the Southern Philippines and to the Indonesian Archipelago and the Malay Peninsula. Indeed, from the twelfth century, long before the Europeans, Arab merchants mingled with Chinese and Indian merchants in the ports of Mindanao, Java and Sumatra...

Physical map of Myanmar

Current administrative map of Myanmar

Physical geography has had (and still has) a strong influence on the diverse history of South-East Asia. The mountain ranges have contributed, on the continent, to the formation of state borders: they separate in particular South-East Asia from China, define the northern limits of present-day Thailand and Vietnam - the Annamite chain also separating the latter country from Laos… We talk about natural borders, but they were not historically necessary, inevitable borders.

Myanmar is presented here as a case study. The entire terrestrial periphery of the country is made up of mountain ranges in the shape of a “horseshoe” overlooking an enclosed, well-defined space: the Irrawaddy basin. This river has its source in the country itself and the control of its waters is not, as is often the case elsewhere, the object of recurrent geopolitical conflicts. The neighboring Mekong basin, on the other hand, is at the same time an axis of civilizational contacts, communications, exchanges and a place of conflicts between China, Vietnam, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia, which have important ecological and demographic consequences (the majority of Laos live at present in Isan, North-Eastern Thailand). [11]

The map of mainland South-East Asia has constantly changed over the centuries. It is mainly in the two spaces delimited by the mountain ranges that the formation of political entities, pre-colonial kingdoms, their decline and their expansion, peaceful or warlike, took place over the centuries. In the basin of the Irrawaddy, after many vicissitudes, the unification of present-day Myanmar emerged in the eighteenth century - the price of the massacre of many of the Mons. At its peak, the Konbaung dynasty was able to briefly conquer, in 1767, the capital of Ayutthaya, in present-day Thailand. In return, the latter could have established its influence on its western neighbour and the course of history would have been modified [12].

The colonial period

Europeans made their appearance in the region in the sixteenth century, with the capture by the Portuguese in 1511 of Malacca, which controls the sea strait of the same name, between the Malay Peninsula and the Indonesian archipelago. Spaniards, French, British, Dutch and Germans followed… The oceanic geography of South-East Asia suited them, because at that time they were content to establish trading posts in port areas, strategic bases, without seeking to conquer territories [13]. They wanted to control the trade in precious commodities (spices) and the channels of commercial communication.

Three centuries after Latin America, the territorial colonization of Southeast Asia by the Western powers began in earnest [14]. The Netherlands, installed in Batavia (Jakarta) since 1619, extended their influence in the archipelago. The British sought to reach China by conquering Myanmar (1826-1885) and the French did the same via what would become Indochina (1859-1893). Having also the Chinese market in sight, the United States entered the dance, by buying (!) in Madrid the Philippines, then by crushing the anti-colonial revolution which had broken out in the archipelago in 1896 [15].

The colonial conquest opened the era of national resistance in Southeast Asia. The direct subordination of societies has common implications for all populations. At the turn of the nineteenth century the region was going through a global change of epoch. However, there were not one or two dominant imperialisms, as in many other parts of the world, but five (Britain, France, Spain, the Netherlands, the United States), not to mention Portugal in East Timor and Germany which retained influence, even though it had not succeeded in establishing a colony of its own.

Each power imposed its own modes of domination in its possessions, giving rise to very different social formations, although all of them were subordinate. On the whole, the strictly colonial period was to last in South-East Asia for less than two centuries – but nearly four centuries in the Philippines.

In Myanmar, the territorial and interethnic conflicts of the past ended up by producing cultural osmosis and a certain mutual tolerance. [16] London, ruler of the country after six decades of wars, rekindled tensions by implementing its traditional divide and rule policy. The colonial authority created two separate administrative territories. On the one hand, the central region, which it developed (rice-growing, etc.). On the other, the ethnic zones, largely left to their own devices, where it intervened very little. It also used Indian troops and the Karen national minority to break down social resistance.

The country had become a province of British India. The authorities favoured the arrival of Chinese and Indian traders, dispossessing the Burmese. Since the colonial state was in need of an abundant labour force - to develop the commercial cultivation of rice and run its administration, it organized in the second half of the nineteenth century, the massive installation of migrants from India (Hindus and Muslims) [17]. As a result, despite an ancient presence of different Muslim populations in Arakan, Muslims as a whole could subsequently be associated by xenophobic movements with British imperialism, with tragic consequences.

Colonization also anchored a form of “segregation” of which the British Club was a symbol. For François Robinne, Mikael Gravers restored on this subject the systematic link between past and present, established with reference to the work Burmese Days by George Orwell (1934) by bringing this notion of segregation “closer to the boss/client relationship and its stereotypes - ethnic, religious, or cultural - on which the system set up is based today, as it was in the past.” [18]

This colonial order aroused resistance, which also resonates with the present. The best known of these was, in the 1920s, the civil disobedience movement, the memory of which has been revived today [19], namely a vast movement to boycott the colonial order of that time, as today the military order. Buu associations (a word which means “No”) proliferated, advocating non-cooperation: refusal to pay taxes, to register trade licences, boycott of imported products… The repression was very violent. Another example: the peasant and nationalist revolt of 1930 initiating the Dobhama Asi-Ayone (We, the Burmese) movement, whose members took the title of Thakin, the masters, a real challenge to the colonizer.

World War II and its aftermath

In addition to the resistance with Buddhist references in the interwar period, there were a range of modern currents linked to various conceptions of socialism, Marxism and Communism (in the wake of the Russian revolution in particular and with the return of students from Britain). The best-known organizations were centralized, verticalist, but intellectuals also developed conceptions valuing an expression “from the bottom up”, rather than “from the top down”. [20]

This was the time, too, when many Asian nationalists met in Japan. In China, the Japanese army had been engaged since the 1930s in a merciless war of conquest. Imperial Japan had nevertheless succeeded in presenting itself, in the eyes of East Asian nationalists, as a power paving the way for the national liberation of the countries of the region.

Tokyo provided (outside the archipelago) the military training of “thirty comrades”, namely the executives of the future Burma Independence Army. The latter would subsequently bear several successive names, including that of the Burmese National Army (BNA). It was commanded by Aung San (Aung San Suu Kyi’s father), himself from the Dobhama Asi-Ayone movement, who in 1939 founded the Communist Party of Burma (CPB).

In 1942, the Japanese invasion of the country began with the support of the Burma Independence Army. In contrast, most of the ethnic minorities sided with the British, which created a wedge between them and the Bamar nationalists (of the majority ethnic group) who suppressed the Karen people, denouncing their “betrayal”. In 1943, a puppet government was established with Aung San as Minister of War and Chief of the Army. However, finally realizing that the Japanese were behaving as a new occupier, he founded the Anti-Fascist People’s Freedom League (AFPFL) and in his turn went over to the British. On March 27, 1945, the Burmese army rose up against the Japanese. Thus, on 15 June 1945, in the victory parade, the flags of the United Kingdom and of the Burmese resistance were flown together. On July 19, 1947, Aung San and six other members of the provisional government were assassinated by a far-right leader after the conclusion of the Panglong accords [21] with the ethnic minorities. Independence was formally proclaimed on January 4, 1948, giving birth to the Union of Burma (official name of the state), of which U Nu was the Prime Minister until 1962.

The new constitution established limited federalism and granted the Shan and Karenni states the right to separate from the Union after ten years. The Karens, to whom London had promised independence, resumed the armed struggle. More generally, the “question” of the ethnic minorities remains unresolved, and it could not be otherwise, given the nature of the dominant political forces in Myanmar, the legacy of past decades

Despite its tortuous history, after independence, the Burmese National Army became a founding myth of Burma and Aung San a titular figure. However, whatever the popular roots of the CPB, there was not in Burma a long process combining people’s war, national liberation struggle and social revolution as in China. Aung San’s movement also remained exclusively Bamar.

Three words are used in French, only one of which belongs to the current language: the Burmese, usually meaning all the inhabitants of Burma. The term “Bamar” refers precisely to members of the majority ethnic group occupying the plains. The name Myanmar, widely used today in English, is a synonym of Burma [22]. It has the advantage of removing any ambiguity by making it possible to recognize the country’s national plurality - it is “fair”, but unknown to the general public, even though it is beginning to spread beyond academia, in activist circles.

The question is not secondary. The view of the historically dominant left tradition in Burma, as embodied by Aung San (and extended by his daughter Suu Kyi), is that of the Bamar social elite, namely an ethno-nationalism that refuses to recognize the plurality of the country and perceives “the other” as an internal threat or external interference. The objective affirmed by the National League for Democracy, marrying socialism and Buddhism, is done without taking into account that a significant part of the population is not Buddhist. It has been unable to offer ethnic minorities a common economic and social development plan that meets their specific needs.

The tradition of this left is both authoritarian and reformist. It nourishes a very “realistic” conception of the power struggle, monopolized by the apparatuses, suspicious of the development of autonomous social movements. In this context, making the army a founding myth, expression and guarantor of the liberated nation, was not without consequences.

A new Burma (Myanmar) may be born tomorrow at the end of the present terrible ordeal, but it will have to break with what was the dominant heritage of the socialist and communist movements in the aftermath of the Second World War, even if it means rediscovering other lesser-known roots.

Towards the military dictatorship

For specialists (I admit my total incompetence in this area), the place of power, identified with a religious order, also refers to Buddhist cosmology. The regime guarantees a balance which cannot be upset at the risk of disturbing the order of the world. This concept, developed by the “club” of General (and future dictator) Ne Win, is cultivated in a dialectic of unity or chaos, according to which “without centralism, society tends towards anarchy”. For Mikael Gravers, the culmination of this logic leads to giving a quasi-religious form to nationalism, yet “nationalism is not religion and neither nationalism nor religion is as such an agent of history. Nationalism is a reductive designation for the process, its models and its strategies” [23]

Even from a Western point of view, Myanmar was not a “backward” country (a term which, in general, it is best to be wary of). The country was enjoying relative prosperity, it was the leading exporter of rice in South-East Asia, its education system was renowned, and the literacy rate was very high. In the 1940s and 1950s, Rangoon University was one of the most renowned in Asia. As in other countries of the region (Pakistan…), poetry occupies an important place in Bamaric and Buddhist culture, which was also influenced through colonization by English literature [24].

However, the army was tearing itself apart. A period of civil war and instability began, from which Ne Win emerged victorious in 1962, following a bloody coup. He established a dictatorship that defined itself as socialist (many regimes that were in no way socialist declared themselves to be so at the time), but also, it should be said, anti-communist. It was then that the matrix of military regimes was formed, of which the current junta is the heir.

Ne Win isolated the country, closed it to foreign trade and massively nationalized for the benefit of the army. Tatmadaw became the backbone of state power in all areas. A large number of workers was employed by the state (hence the importance, even today, of civil servants). It is pursuing the Communist Party, which has established bases on the borders of China, and it is waging a fierce repression against certain ethnic minorities, including the Karen.

Myanmar was regressing historically. The “management” of the country by the dictatorship was turning into a disaster. Poverty was growing explosively and the education system was crumbling. Poetry was kept under a leaden shell. On the other hand, numerology [25], which is part of the Bamaric culture, was actively promoted. After thirty years, Ne Win had to give up power. But the power of the army continues. Till today.

Resistance movements

Let us look back over history. [26] Most of the waves of anti-dictatorial mobilization have had as their spark or background a socio-economic crisis.

The 1988 crisis. In that year, Ne Win withdrew from circulation the denominations of 25, 35 and 75 kyat (the name of the Burmese currency), causing the sudden impoverishment of a population which was already struck by economic difficulties. The politicised students were also mobilized after police released the son of one of the leaders of the single party in power, the Burma Socialist Programme Party, who had been involved in a fight. There was an explosive reaction when riot police killed a student during the protests against this preferential treatment and against demonetization.

The movement spread to other social sectors - including monks, civil servants and members of the police. On August 8, 1988, hundreds of thousands of Burmese demonstrated in the country. The repression was bloody and the number of deaths gigantic, estimated to have been at least 3,000 between March and September. Many took refuge in Karen State, where they were welcomed and sometimes given military training by the Karen National Union (KNU).

The movement was broken, but Ne Win must had to resign. A new “Council of State for the Restoration of Law and Order” was formed, headed by General Saw Maung, then in 1992 by General Than Shwe. Faced with international opprobrium, the junta promised to organize multiparty elections, probably convinced that it wou;dwin them, because it believed that it embodied the historical legitimacy of the Independence Army. It was mistaken!

The 1990 elections. Aung San Suu Kyi (Aung San’s daughter) entered the electoral arena. She mobilized crowds and founded the National League for Democracy. It was a fight for historical legitimacy. More deeply, the elections were the occasion to express a massive rejection of the military regime. In May 1990, while Suu Kyi was under house arrest, the LND, thus deprived of its leader by the regime, won 392 of the 485 seats in Parliament!

The junta annulled the result of a poll that it had itself organized. NLD parliamentarians were repressed, Suu Kyi remained under house arrest. The opposition founded, in response, a National Coalition Government of the Union of Burma (NCGUB), made up of deputies elected during the legislative elections. But this Burmese government in exile was not recognized. The junta continued to represent Burma in international forums.

Faced with the crises of 1988 and 1990, the “international community” was divided between the supporters of the policy of sanctions (not effective enough to roll back the junta) advocated by the United States, the European Union and Canada, New Zealand and Australia - and proponents of a “constructive engagement” that preserved the status quo.

2007 and the “saffron revolution”. In August 2007, the junta decided to increase the price of fuel without warning (a type of measure which leads to a general increase in prices and which has been the cause of real revolts in many countries). Former student leaders of 1988, who had been released after long years in prison, took up their activity again, mobilizing at the same time against rising prices and for democracy. When they were arrested again, Buddhist monks took over, especially since they were directly impacted by the worsening social crisis. They depend on food donations, collected every day in the morning, to feed themselves! They founded the underground organization All Burma Monks’ Alliance. They demanded the release of political prisoners and the opening of a dialogue with democratic forces. Some monks even went to Aung San Suu Kyi’s home, where she remained under house arrest.

The demonstrations grew in scale during the month of September. The repression this time caused few deaths (international attention was focused), but the regime attacked journalists, including those of the Democratic Voice of Burma, a Burmese audiovisual media whose images were reproduced in the whole world. Arrests were increasing. The curfew was declared. The monasteries were the object of night raids. At the beginning of October, the opposition movement was exhausted.

The junta again organized elections in November 2010, which this time were neither free nor transparent and which the NLD boycotted. The military party, the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP), won a victory without legitimacy. It had to negotiate and to free Aung San Suu Kyi. The legislative elections of 2012, 2015 and 2020 were all won hands down by the NLD. The army resigned itself to a sharing of power, but after having imposed, in 2008, a Constitution guaranteeing the perennity of its own power (see the introduction to this article). Suu Kyi, de facto head of the Myanmar government from April 2016, endorsed the policy of “constructive engagement”, it seems, in the hope (which turned out to be illusory) that Tatmadaw would accept finally a constitutional reform contrary to its own interests.

The particularities of the Burmese army

Considering what the Burmese army is, could it be otherwise?

The first question that was posed after the coup of 1 February was: why did the army decide to do that in a country where it already controlled the essential levers of power? In terms of general political orientation, no disagreement with the NLD justified the break. A small part of their motivation was to guarantee the future of General-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing, whose retirement age was approaching; a lot of it was about regaining control when, as a result of successive electoral failures, Tatmadaw’s political legitimacy was declining in favour of the National League for Democracy of Aung San Suu Kyi. The Burmese military chose to play Trump: we never envisioned that this could be so, so it did not happen.

On the strength of its electoral legitimacy, the NLD wanted to move the lines within the unequal balance of power by gradually expanding the sphere of competence of civilian government. Suu Kyi had been careful not to question the generals’ sources of enrichment and had obviously not anticipated the violence of their reaction. Tatmadaw has in fact decided to put an end to their collaboration, once and for all, without any sharing of prerogatives. The coup of February 1 put an end to coexistence between the army and a government elected after free elections, which was inexorably giving a majority to a competitor party, the one led by the “State Counsellor “Aung San Suu Kyi. More generally, the junta attacked the entire “civil society”, which had developed following the economic opening of the country a decade earlier: associations and trade unions, civil rights, etc. If the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) was immediately formed the day after the putsch, it was not only to protest against the overthrow of an elected government, but because their freedoms were being directly targeted - the precedent of 1988 had not been forgotten.

The second question that was being posed, abroad, the day after the putsch, concerned precisely this question: would the generation of generals represented by General-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing act with the same brutality as the previous one or would it be more e moderate. We quickly got the answer. Tatmadaw has not changed.

Tatmadaw cannot change and that is the problem. Comprising at least 350,000 men, it is a state within a state, a form of “total power”, a world apart. The professional backbone of the army (which also recruits forced conscripts from each family) represents a social elevator for young people educated in the cult of the chief. The officers and their families live in closed circuit, and they benefit from privileges which make of them a caste, distant from society and floating above it (it is the same, by the way, for sectors of the globalized bourgeoisie). The officer corps derives immense benefits from its control over the state bureaucracy and over two large conglomerates, the Myanmar Economic Corporation (MEC) and the Myanmar Economic Holdings Limited (MEHL) [27], as well as from trafficking in precious stones and wood. They sometimes constitute quasi-monopolies and encompass many sectors: aviation, banking and insurance, energy, pharmaceuticals, imports, construction, tourism, mines (notably jade), etc.

The army grants authorizations and licences in many sectors of activity. The “khaki economy” is not unique to Burma, far from it, but it is particularly developed here, giving birth to a “clientele capitalism”, an instrument of corruption and control. Tatmadaw’s power is not organized only at the national level. The army constitutes a parallel authority which doubles, from top to bottom, the civil administration, giving it at each level a strong capacity of influence over society. Even in times of crisis, it is uncertain to hope for significant defections within it (unlike the police, where they have occurred, and forced conscripts who live under the threat of reprisals if they refuse to obey orders). Past experience gives it confidence in its ability to last, in the face of stigma and (quite relative) international sanctions. It knows that when times are hard can count on the support of China and Russia. The junta thinks they have time on their side

The number of defections seems to be on the rise, but remains marginal. Internal rivalries between commanders could divide the general staff, however, especially if the cost of sanctions becomes so high that the khaki economy goes into crisis and its profits collapse. This is theoretically possible, but it has never been the case in the past.

Instances of Buddhism

In Burma as elsewhere, the Buddhist currents of reference can, depending on the period or the issue, cover the entire political spectrum. Monasteries have engaged in democratic contestation, as in 2007 or today in Mandalay. Other movements may be situated on the fascist far right, as was the case with the Organization for the Defense of Race and Nation (Ma Ba Tha) which played a key role in the genocide of the Rohingya. As for the official authorities (the Sangha), they are not supposed to engage in politics, but they traditionally provide their support to the regime in place, without making its dictatorial character a bone of contention. After the coup of 1 February, the general staff took care to woo more than ever the religious hierarchy.

The monastic order has 500,000 members divided into 9 sects [28] In the beginning, faced with the crisis sparked by the coup of February 1, the clergy remained discreet. Groups of bhikkus (monks) certainly joined the demonstrations, waving placards, but this remained anecdotal - they were less numerous than the pro-army monks who publicly supported the putsch a few days before it happened. However, under continued pressure from the civil disobedience movement, the conservative alliance between religious authorities and the military regime began to crack seriously. One of the most influential figures, Sitagu Sayada, very close to the general-in-chief, was subjected to a wave of criticism on social networks. His sect, the Shwe Kyin, ended up calling on the military to be more restrained in repression. Pro-democracy monks are now making their voices heard, especially in Mandalay, Burma’s second urban centre, where several monasteries have entered into open dissidence. In this city, every day, in the afternoon, the monks take the lead of a lightning demonstration, knowing that their presence constitutes a protection.

Most recently, the president of the National Sangha Committee - a structure set up by the junta where it appointed “venerables” of its choice - announced that it was ceasing all its activities. Bad news for the junta!

Monasteries in Mandalay and monks, mostly young, defied religious edicts that prohibit them from political activity in order to proclaim their condemnation of the generals. However, the pro-military faction of the clergy remains powerful, claiming that the regime protects Burma’s Buddhist identity against the supposed threat of a slow takeover by Islam. Among this group we find the movement Buddha Dhamma Parahita Foundation, extension of Ma Ba Tha (banned in 2017) led by Wirathu / Parmaukha, the ultranationalist and very influential monk who pursued with his hatred the Rohingyas until the genocide. In his eyes, Aung San Suu Kyi paved the way for “the extinction of our religion, our ethnicity and the whole country”. [29]

Aung San Suu Kyi and the future of the NLD

The personality of Aung San Suu Kyi and her dominant role in the National League for Democracy has occupied a considerable place in the political history of Burma (and the solidarity movement) in recent decades [30]. Those who know her (which is not my case…) have sometimes contradictory opinions in this regard. She is very courageous, undeniably. But, just as unmistakably, there has been a real misunderstanding about the nature of her democratic commitment. The image of the icon, Nobel Peace Prize winner, was shattered when she defended tooth and nail, in the international arena, the intervention of the army which led to the genocide of the Rohingyas, who were massacred, forced to flee (750,000 refugees), and who have become a stateless population with no future. If a trial finally opened against the military responsible for this tragedy, Suu Kyi would be in the dock for complicity.

For some people, it seems, her positioning was only political calculation in the complex game she was playing with the military. For others, she did not want to tarnish the reputation of an army of which her father was the founder. In view of the virulence and consistency of her discourse (she refused to pronounce the name of the Rohingyas, considering them to be Bangladeshi) and the obstacles she put on their return, these explanations seem to me to be quite insufficient, even if they are not justifications.

We can hope that the dramatic (and very specific) story of the long persecution and genocide of 2017 against the Rohingya, a predominantly Muslim population living in Rakhine (Arakan) state, can finally be revisited by the young generations.

As we have already noted, Aung San Suu Kyi belongs to the Bamar social elite, whose views on ethnic minorities she shares, and, it seems to me, fits into the dominant ethno-nationalism. It is democratic insofar as it advocates the preeminence of a civilian government. It is also authoritarian, does not empower civil society and does not like alternative checks and balances to the NLD. She was engaged before the coup of February 1 in a complex game of pressures-negotiation over which she wanted to keep complete control, without the autonomous intervention of the civil society whose freedoms she “frames”.

The current crisis may be reshuffling the cards. Even if in Bamar country, the resistance relies heavily on the electoral legitimacy of Suu Kyi, the NLD and the CPHR, hundreds of thousands of people must contribute to the daily organization of the struggle in their localities. The Civil Disobedience Movement was born outside the control of the League - and a new generation of cadres must be forged within the NLD itself (Aung San Suu Kyi is 75 years old).

The evolution of the NLD and the apprenticeship of political pluralism in the anti-dictatorial camp are among the major questions opened by the present crisis.

Bamars and National Minorities

Another big question is the relationship between the Bamars (68 per cent of the population) in the centre and the members of national minorities on the outskirts of the Irrawaddy basin. It runs through, as we have seen, the entire history of Burma. One has the impression that for the first time, the present conditions make possible a real, shared federal solution, giving content to the official name of the country: the Union of Burma or the Republic of the Union of Myanmar, which recognizes the existence of 135 ethnic groups.

Administrative divisions

Info-Birmanie

A new combative generation, the so-called “Generation Z”, very young (high school students), can break with past prejudices. The Civil Disobedience Movement has asserted itself in almost all regions of the country and all the states of national minorities. It seems to me that never before has this been true to such an extent.

Admittedly, there is a gap between spontaneous demonstrations against the coup d’état and the positioning of the official authorities (parliaments) of the national states which have often remained in an attitude of waiting to see how things will turn out.

The first objective of an ethnic minority is to be effectively master of its own home, to have control over its historic territory, not to be dispossessed of it. Depending on the situation, it can conclude or denounce ceasefire agreements with the central power. In this perspective, the authorities of each ethnic group can go it alone or, on the contrary, build a common front to exert more weight together, for example to impose a real federal system. Today we are probably in an in-between situation. [31] Another factor to take into account is that there is usually more than one armed party and movement in an ethnic state.

The Karen State (or State of Kayin, bordering Thailand) is at the forefront in opposition to the dictatorship. The Fifth Brigade of the Karen National Union (KNU) represents one of the largest armed groups in the country. It immediately declared itself ready to welcome and protect the underground members of the CPHR, then of the NUG. Heavy fighting broke out, with the army bombarding the Papun district. More than ten thousand people fled their villages, some taking refuge in Thailand, from where they were initially turned back [32]. However, the harshness of the conflict has opened a policy debate in its ranks, in preparation for its next congress.

In Kachin State, in the far north, with India and China as its border countries, the Kachin Independence Army attacked a remote army post in a measure of retaliation after it had killed demonstrators of the civil disobedience movement. In the town of Shwegu, more than 400 government employees, including police officers, are said to be involved in the movement. [33]

In Arakan (Rakhine State), the junta removed the Arakan Army (AA) from the list of terrorist organizations and a ceasefire was signed. However, the AA threatens to break it if the army continues to attack the democratic opposition in its territory.

The same is true in other minority states. The self-defence forces remain in a wait-and-see posture, but can react when the army assassinates demonstrators.

As has been pointed out, for national minorities the question of federalism is essential. In the face of adversity, the National League for Democracy is (finally) committed to effectively taking this question into account. If this commitment takes shape, it can be a geopolitical game-changer in Burma itself. Otherwise, some minorities threaten to demand independence.

Another crucial question is that of citizenship. In particular, it is traditionally defined through membership of a recognised ethnic minority, which, according to the anthropologist François Robinne, tends to freeze ethnic divisions and the geopolitics of military conflicts in a dangerous way. [34]

The underground constitution of the National Unity Government (NUG) is from this point of view a big step forward. Its composition is indeed multi-ethnic. [35]

The NGU issued its “Policy Position on Rohingya in Rakhine State” on 3 June 2021, which recognises the seriousness of the wrongs done to this minority and the need to remedy them, commits to recognising true federalism to be defined in cooperation with minorities, and announces a new law that must “base citizenship on birth in Myanmar or birth anywhere as a child of Myanmar Citizens”. [36]

For the time being, China continues to influence the positioning of the northern border states and, in particular, that of the very powerful United Wa State Army (UWSA), the best endowed with weapons. As for the junta, it does everything to co-opt the social elites of the minorities and attach them to itself. A complex standoff is underway, the outcome of which will help shape the country’s future.

The geopolitical impact

If the civil disobedience movement had been quickly broken, the junta probably could have got away with it internationally without too much damage. In terms of investment and trade, the integration of the Myanmar economy is above all regional: Singapore, China, Thailand, India… (the first Western country concerned is Great Britain). The golden rule of ASEAN [37] is non-interference in the internal affairs of its member countries (this association is a club of authoritarian regimes). This is also the traditional position that China defends in the UN Security Council. Western firms (of which Total is a typical example) play a considerable economic and financial role, but they are used to working without qualms with dictatorships.

The civil disobedience movement has not died out and has suddenly changed the rules of the diplomatic game. China’s attitude bears witness to this. In “normal” times, it would have been content, with Russia, to oppose in the UN Security Council any “interference” in the internal affairs of Myanmar (the Chinese press had started by describing the putsch as a big cabinet reshuffle). This time, although China was opposed to the council condemning the junta, it had to accept it expressing its “serious concern” and calling for the “immediate release” of all those detained as well as the end of restrictions on journalists and activists.

More generally, Beijing must reconcile conflicting interests, which becomes difficult in times of acute crisis. Aung San Suu Kyi had excellent relations with Xi Jinping; she is now incarcerated and her trial for high treason has been announced. The CCP considers the border territories occupied in the north by national minorities to be part of its geostrategic security perimeter and sells them arms. It nevertheless needs to secure the very significant investments it has made in the country, which requires an agreement with the military in power. It demands that the latter protect the Chinese textile companies established in Burma (they are being set on fire as a retaliatory measure against its support for the junta), as well as the oil and gas pipelines which carry vital energy from ports in Myanmar. Access to the Indian Ocean remains a major objective, the “Myanmar corridor” (in addition to the Pakistani “corridor”) offers it one. In these conditions, the “stability”, of which for the moment there is no sign, of the country is very probably its priority.

Wikipedia

Burma (Myanmar) gives direct access to the Indian Ocean, that is to say to the west of the Strait of Malacca which “locks” the South China Sea.

There is no love lost between Beijing and the very anti-communist Tatmadaw (there is no longer anything “communist” about the Chinese state side, but it is not certain that the Burmese generals have realized this). However, in hard times, the putschists can count on the more or less enthusiastic support of China, Russia, Vietnam and Modi’s India. These countries were all represented on the platform during the celebration of “Army Day”, Beijing a little more discreetly than Moscow. The junta has appointed a government which includes Burmese civilian figures known for their links with the CCP (in the field of economic or cultural cooperation) [38] A measure aimed, probably, at facilitating the deployment of the Chinese protective shield.

It is possible that Xi Jinping had something to do with the coup of February 1 (could he have prevented it?), But it is certain that being able to play the Chinese card has been considered a major asset by the junta, encouraging its determination to stick to its guns. It can count on its two main suppliers of arms, China and Russia.

Punishments

Some sanctions that were taken in the aftermath of the putsch hurt, such as President Biden’s freezing of a billion dollar transfer from the US Federal Bank to Myanmar. Others show what it would be possible to do and are an encouragement to international solidarity which can, in the present context, be effective. Overall, however, the measures target only members of the junta or sales of arms destined for the forces of repression; they do not concern the economic empire of Tatmadaw and do not apply, for the time being, to the main firms trading with the state and the khaki economy.

As early as 2017 and the persecution of the Rohingyas, companies had started to leave Myanmar, such as the cement manufacturer LafargeHolcim. The Franco-Swiss company announced in the summer of 2020 the liquidation of its Myanmar subsidiary, when it was cited in the report of independent UN experts as having contractual or commercial links with the army. The Japanese brewer Kirin, for its part, announced in early February that it intended quickly to end its relations with the Burmese army (it operates two breweries in the country). However, the European Union remains very reticent on this question, as do, in particular, French companies.

The Accor hotel group is playing the innocent, while it is associated with a conglomerate of the “khaki economy” in the construction of a five-star hotel with 366 rooms in Yangon, the Novotel Yangon Max. Its partner is the Max Myanmar Group. This company helped the army to build infrastructure preventing the return of the Rohingya to their lands, in Rakhine (Arakan) state after the persecutions of 2017 which had led to their forced exodus. In 2019, independent UN experts concluded an investigation by ruling that Accor’s partner should be the subject of a criminal investigation which could lead to it being prosecuted for contributing to a crime against humanity. No less than that!

Since 1992, Total has operated part of the Yadana gas field, off the coast of Myanmar. [39] In 2020, the President of the country awarded Moattama Gas Transportation Co, the subsidiary of the international group Total registered in Bermuda, the “prize for being the biggest taxpayer” in the “foreign companies” category for the 2018-2019 fiscal year. More generally, Total is the largest, or one of the largest, financial contributors to the Myanmar state, paying it $ 257 million (€ 213 million) in 2019. From now on, as denounced by the ONG Justice for Myanmar, “foreign investors will finance a brutal and illegitimate military regime, as was the case before 2011”. The NUG, which represents the continuity of the elected parliament, therefore the legal authority of the country, demanded from Total that it stop paying income in any form whatsoever to the junta and the army. By refusing to do so, Total endorses the putsch.

Canal + (French television group, subsidiary of Vivendi) has a holding company registered in Singapore. It broadcasts, among other things, the state-run Myanmar Radio and Television (MRTV). It claims to be technically unable to remove it from its list (which Facebook did).

Other French companies are looking to enter the Myanmar cybersecurity and biometric identification systems market. In fact, the number of French and European companies engaged in Burma with the state or the khaki economy is very important. They should not be allowed to continue discreetly pursuing their business.

The United States has (unilaterally) equipped itself with a nuclear weapon in terms of sanctions. Any transaction carried out in US dollars anywhere in the world may fall under US justice if it is contrary to Washington policy. This weapon has already been used against, for example, banks or companies doing business in Iran and the fines demanded are reaching new heights! Refusing to pay means being banned from being present in the United States… Joe Biden said he was studying the possibility of using this procedure in the case of Myanmar… but has not done so to date.

The European Union and sanctions

The European Union has camped itself firmly on a reductive definition of sanctions and that does not appear to be changing. According to one diplomat, the foreign ministers of the 27 EU member states said on Monday February 22 that they were “ready to adopt restrictive measures targeting those directly responsible for the military coup and their economic interests.” “Sanctions can only target certain administrations or certain people, military or not, but we must first collect the evidence and constitute a legal basis for these sanctions.” [40] As Sophie Brondel, from the Info Birmanie association, emphasizes, “We must not only target the military, whose savings are often placed in Singapore, but the large companies which strengthen their power.”

A new set of sanctions is being prepared at the UN and by various governments; we will have to see what they amount to.

Our solidarity

To conclude, it is high time for solidarity in France to assert itself on all levels: political parties, associations and unions have to take positions, put pressure on the French government and the European Union, put companies guilty of trading with the khaki economy on the spot, search for direct links with the social actors of the democratic resistance...

Total is a multinational group, but also, and above all, a French company in which the state is a shareholder. This firm is much more than that: the arm of French imperialism, in particular in Africa, where it plays a role that is not only economic, but geostrategic in the support which Paris brings to the dictatorships of francafrique. As a result, even if Myanmar does not belong to France’s traditional international political intervention space, we French people are involved in the Myanmar crisis and our responsibility is directly engaged. Even if this was not the case. we would still have to mobilize in support of the peoples of Myanmar who are suffering from exceptionally brutal violence.

There are subjects, in France, on which the left remains (almost) silent, such as French nuclear weapons and the research which continues on their “modernization” (with a view to making their use politically acceptable). Total is one of those blind spots that it is inappropriate to talk about. Francis Christophe wrote a powerful article on Total’s influence in France. [41] He concludes that Anne Hidalgo, mayor of Paris, has just appointed to the city’s international affairs department a former director of public affairs for Total: Paul-David Regnier: “his appointment, with such a profile, as the person responsible for the international image of a city ruled by a majority including EELV (the Greens), has elicited no public comment. This also gives the measure of Total’s influence, and the omerta that accompanies it. The wall of silence is beginning to crack, moving beyond the activist networks. Thus, the daily Le Monde devoted two pages on May 4 to an investigation of the oil giant. [42]

A member of EELV did indeed raise a question in Parliament on Total to which, contrary to the usual procedures, she has not received an answer. The New Anti-Capitalist Party (NPA) immediately attached great importance to the Myanmar crisis. The same goes for the International Trade Union Network for Solidarity and Struggles. For its part, ESSF provides on its site daily information on the country, its history and the way the situation has been evolving. Our association launched an appeal for financial solidarity intended for components of the Civil Disobedience Movement [43]

People from Myanmar residing in France have created an association - the Burmese Community of France - asking that the legitimate authorities of Myanmar be recognized. Last May 10, a tribune was published in Le Monde by a group of researchers and specialists on Myanmar, calling on France to “recognize without delay the National Unity Government (NUG)”. [44]

The Myanmar junta found itself in a situation of great weakness immediately after its putsch, due to the massive entry into civil disobedience of the bulk of the population. The coup was thwarted. Unfortunately, due to a lack of broad international solidarity and effective sanctions, the junta was able to gradually regain the initiative. Time is currently playing in its favour; international bodies have not officially recognized the GNU. [45] Resistance in Myanmar is now digging its heels in for the long haul. Solidarity must do the same.

What is at stake in the Myanmar crisis is of an international dimension. South-East Asia is at the crossroads of the Asia-Pacific region, whose geostrategic importance has become major: it is there that the face-to-face between the United States and China is being played out primarily. It is also there that in reaction to the hardening of dictatorial regimes, a wave of democratic resistance began, from Hong Kong to Thailand. Myanmar is continuing this wave. For many reasons, progressive movements in countries like the Philippines (where the military is once again waging an all-out war against anything it chooses to consider subversive and where ethnic minorities are also going through a violent process of dispossession) see the struggle of the peoples of Myanmar as their struggle. The outcome of this struggle will have implications across the region.

Pierre Rousset

Wednesday 26 May 2021

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook