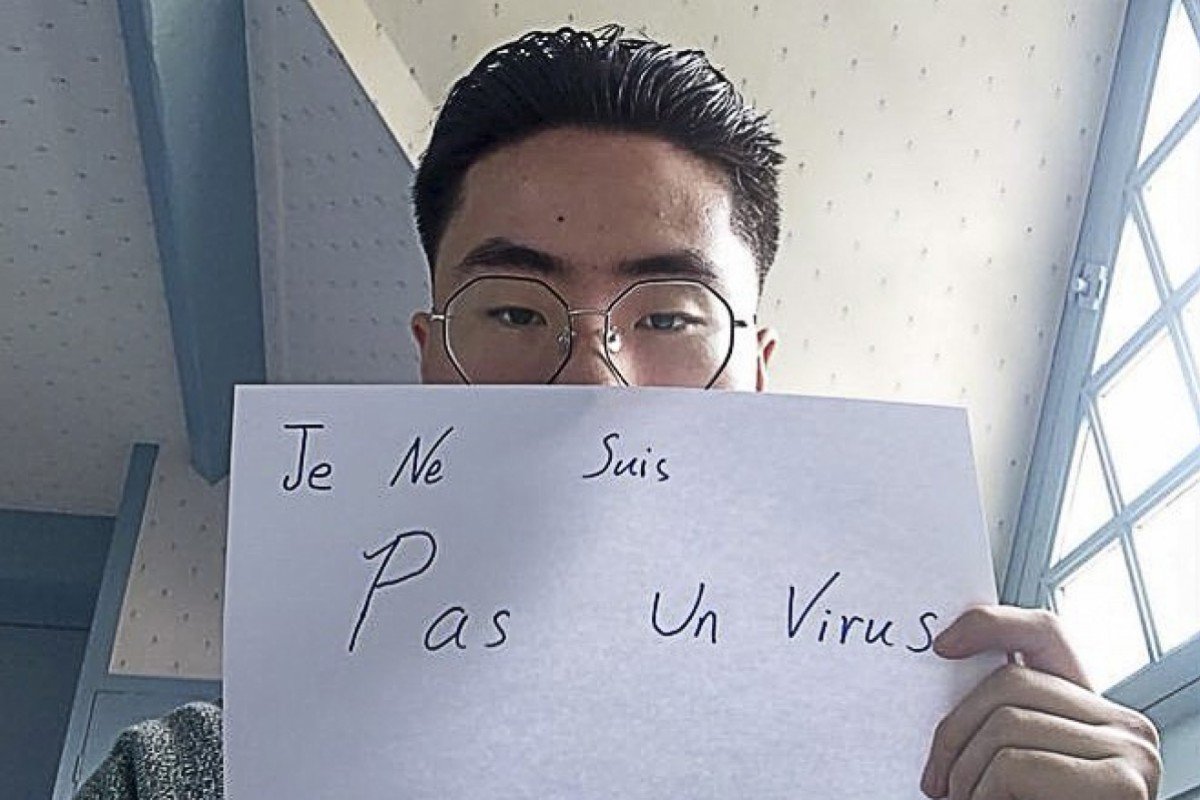

Social media campaigns such as “Je Ne Suis Pas Un Virus” (“I am not a virus”), a hashtag started by Asian people in France to combat xenophobia, have inspired others to take a stand against the growing climate of fear and mistrust. Photo: TwitterSocial media campaigns such as “Je Ne Suis Pas Un Virus” (“I am not a virus”), a hashtag started by Asian people in France to combat xenophobia, have inspired others to take a stand against the growing climate of fear and mistrust. Photo: Twitter

Fear of the ‘Yellow Peril’ seems to have returned as the novel coronavirus spreads globally. The outbreak has unleashed an underlying prejudice against Asians, in particular Chinese.

Time and again, I have read stories on my social media groups about how fellow Chinese have experienced verbal and even physical abuse in Britain, simply because of their race. Some were told to go home. One student in Sheffield was harassed for wearing a face mask. A Chinese doctor’s practice had a coronavirus sign painted over it.

Around the world, anti-China sentiment is bubbling over. Some restaurants in Vietnam, Japan and Italy are refusing entry to Chinese. A Danish newspaper, Jyllands-Posten, courted controversy by publishing a cartoon version of the Chinese flag with viruses in place of the five stars [1].

On February 3, The Wall Street Journal ran an op-ed by Walter Russell Mead titled “China is the Real Sick Man of Asia”, with the subtitle: “Its financial markets may be even more dangerous than its wildlife markets.”

Whatever the author’s issue with China, it is shocking that a mainstream media outlet would use such a headline, which insults not only the Chinese government but also ordinary Chinese people. I wonder whether whoever came up with it really understands the historical context of the term sick man of Asia.

Britain’s Chinese community faces racism over coronavirus outbreak

It actually refers to the sickly state of China in the late 19th and early 20th century, bullied by Western powers and plagued by internal divisions.

This term is strongly associated with events regarded as a national humiliation, such as the Opium war, a series of unfair treaties the Qing government signed with Western nations, pressured by their superior weapons, and the burning of the Old Summer Palace in Beijing. To this day, the scars caused by that humiliation run deep among Chinese people.

For them, “sick man of Asia” is a derogatory reference, and triggers painful memories of the country’s darkest days. Back then, the term also referenced the poor physical health of Chinese people, thanks to the appalling lack of hygiene and overwhelming poverty.

As China was the sick man of Asia, so Chinese were regarded as the “Yellow Peril”. At the tail end of the 19th century [2], German emperor Kaiser Wilhelm II reportedly came up with the term after he saw, in his dream, Buddha riding a dragon, threatening to invade Europe.

Even if he did not coin the term, Wilhelm popularised the psycho-cultural perception of the so-called civilised world – that is, the Anglo-Saxon empires – in danger of being overrun by the yellow-skinned East Asians (the Chinese and Japanese).

He then encouraged European powers to conquer and colonise China. In 1898, Germany coerced China into leasing it 553 square kilometres in its northeast, including Qingdao, for 99 years. That was another event of national humiliation.

Even before the aggressive German emperor, however, white supremacists in the US had embraced the “Asian menace” theory, demanding that the government bar immigration of “filthy yellow hordes” of Chinese.

The white labour unions lobbied to keep out Chinese, claiming that some Chinese malaises were more virulent than white ones. This led to America’s 1882 China Exclusion Act [3], an immigration law that prevented Chinese labour from entering the US. It was revoked in 1943 but old prejudices persist.

One editorial from 1954, for example, in the influential New York Tribune newspaper, described the Chinese thus: “They are uncivilised, unclean, filthy beyond all conception, without any of the higher domestic or social relations; lustful and sensual in their dispositions; every female is a prostitute, and of the basest order.”

In a 2014 review of the book Perceptions of the East – Yellow Peril: An Archive of Anti-Asian Fear, sinologist Leung Wing-fai explains that: “The phrase yellow peril (sometimes yellow terror or yellow spectre) … blends Western anxieties about sex, racist fears of the alien other, and the Spenglerian belief that the West will become outnumbered and enslaved by the East.”

Some experts have noticed that only certain disease outbreaks have been racialised. Those that originated from China, such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (Sars) and the novel coronavirus, as well as Ebola from Africa, led to a racial backlash. However, this did not happen with the swine flu pandemic that originated in North America or “mad cow disease” from Britain.

When millions of Chinese are suffering, racist headlines and comments are doubly insensitive and inappropriate. It only perpetuates the stereotype that Asians are disease-ridden. Fear and racism feed on each other, and both hinder our fight against the virus.

Lijia Zhang

• South China Morning Post. Published: 10:30am, 16 Feb, 2020:

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3050542/coronavirus-triggers-ugly-rash-racism-old-ideas-yellow-peril-and

• Lijia Zhang is a rocket-factory worker turned social commentator, and the author of a novel, Lotus.

Biased Western reporting on the coronavirus may have a nasty side effect: a new wave of Chinese nationalism

Some Western media outlets have invoked the ‘yellow peril’ in their coverage of a ‘Made in China’ virus. Intentionally or not, such an approach is inciting xenophobia in the West and fuelling a nationalistic backlash in China.

The cover of the German news magazine Der Spiegel warned about a deadly peril to humankind: “Coronavirus Made in China”. The colour of the words “Made in China” signals to the reader the nature of this peril: it is yellow – as yellow as the five stars on the Chinese national flag, to be precise.

The cover photo makes a visual allusion to this flag by showing an Asian man cloaked in red protective gear. He is also wearing a gas mask with yellow air filters, which match the colour of the words “Made in China”. Thus, a false message is proclaimed: the virus that currently threatens so many lives has a nationality; it is Chinese.

Medically speaking, it makes no sense to put a national label on a virus, but journalistically it does. Blaming a specific nation for “making” an illness channels anxiety and directs anger towards a specific target. It politicises a dangerous epidemic by associating it with a national flag.

The cover of Der Spiegel is but a variation of a cartoon published in the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten a few days earlier, which replaced the yellow stars of the Chinese flag with yellow virus particles. Both images express what the French regional paper Courrier Picard dared to say bluntly in a headline: “Le péril jaune?” (Yellow peril?).

Once again, European media outlets large and small are making direct or indirect use of the racist slogan that characterised Western representations of China and East Asia in the 19th century.

Negative representations have long dominated Western reporting on China. It can be argued that this is only fair since such bad news merely reflects bad realities. It can seem morally prudent to highlight shortcomings in a certain country as long as they persist. The long-term repetition of negative news, however, can have a number of unintended negative consequences. [4]

Constant negative reporting eventually creates a negative image not only of a country but also of its people. German football player Sandro Wagner, who moved to China in 2019, said in a recent interview that he was pleasantly surprised by the Chinese people, after getting a negative impression of them from the media. Media reporting can breed stereotypes which, once they have taken root, are hard to shake.

A long-standing negative narrative also perpetuates a tendency, on the part of the media, to cast any news event in a perceived rogue state in a similar political light. The characterisation of the coronavirus as a national product springs from this very mechanism. In one stroke, an epidemic has transformed from a medical issue into more evidence that something is fundamentally wrong with a certain nation.

When, in the face of the coronavirus, a negative national profile is almost hysterically intensified, racist sentiments may well be incited. Already, the virus’ spread is fuelling “racism and xenophobia” in countries including not only Canada and New Zealand, but also Vietnam and Japan, as reported by CNN. French Asians are hitting back with the hashtag #Jenesuispasunvirus (I am not a virus).

Der Spiegel, however, obviously feels no need to refrain from fanning the flames, even though its latest issue came out as the German media reported a violent attack against a young Chinese woman in Berlin.

The plague of fear and prejudice could be just as lethal as coronavirus

3 Feb 2020

Certainly, the Western media cannot be accused of intentionally spreading hatred when reporting negatively on China. From their perspective, they are presenting justified and necessary political and social criticism. Such reporting is intended not only for Western audiences, but also for the Chinese people.

The hope is that such criticism will open Chinese citizens’ eyes and inspire them to make changes for the better. However, this sentiment is not only paternalistic and but also smacks of a new kind of colonialism. In fact, such an assumption might be deeply mistaken and is backfiring on the Western media.

The Western media’s one-note narrative of China is eroding their credibility among the Chinese audiences they seek. Once upon a time, many Chinese people trusted foreign media more than their own, and regarded the West as a haven of free speech. But this is now changing.

Following what has been perceived as one-sided Western reporting on a wide range of issues – from Tibet to Xinjiang, from Huawei to the Chinese social credit system and the recent protests in Hong Kong – the pendulum is swinging. Increasingly, the Western media seem biased, to be catering to certain expectations of political correctness in the West, and consequently, to be lacking in diversity.

The Western media are less and less regarded as a more objective and informative alternative to the Chinese state media, and more and more as just another source of political propaganda.

Persistently negative reporting on China has not pushed the Chinese people to embrace liberal views; rather, it makes many of them feel discriminated against, slighted and insulted. Such feelings only feed defiance, and foster a new nationalism.

This defiant Chinese nationalism in the face of foreign disesteem is in turn encouraged, and appropriated, by the Chinese media and government – who seek to appear as guardians of national honour and strength.

Essentially, sensationalist and borderline racist journalism not only fuels anti-Chinese sentiments in the West but also a new wave of nationalism in China. It runs the risk of contributing to a vicious circle of resentment, counter-resentment and ultimately, conflict and violence.

Hans-Georg Moeller

• Dr Hans-Georg Moeller is a professor in the Philosophy and Religious Studies Programme at the University of Macau.

• South China Morning Post. Published: 9:00am, 7 Feb, 2020:

https://www.scmp.com/comment/opinion/article/3049121/biased-western-reporting-coronavirus-may-have-nasty-side-effect-new

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook