James Michener called the Pacific Ocean “the meeting ground for Asia and America,” a world of endless ocean and “infinite specks of coral” that form a highway between east and west. Indeed, these scattered islands stretching from Papua New Guinea to Easter Island have been an important link between the two rims of the Pacific since at least the 16th century, when imperial Spain’s Manila Galleons sailed between colonial Mexico and the Philippines — bypassing the dominance of its Iberian neighbor, Portugal, in the Indian Ocean.

The gradual emergence of the United States as the premier Pacific power, cemented in the wake of World War II and the subsequent Cold War, involved the establishment of footholds on these vital stepping stones. Today, these footholds remain — either as sovereign U.S.-held territories or freely associated states — but the end of the Cold War reduced these lands’ importance to the United States.

Stratfor has long highlighted, the intensifying great power competition between the United States and China. While geographically remote, Pacific island countries like the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and Palau are one theater in which this global contest will play out.

But with China rising and great power competition heating up, these islands have gained renewed strategic prominence. Beijing’s maritime ambitions center first and foremost on the first island chain that runs from the Kurils through Japan, Taiwan and the Philippines to Borneo, but the second island chain from Japan south to the Northern Mariana Islands, Guam, Micronesia, Palau and Papua New Guinea will be critical in the long term. And given their small size and economic challenges, these Pacific microstates ultimately offer a low-cost opportunity for China to grow its influence and challenge U.S. strategic dominance.

Infinite Specks of Coral

The Pacific islands consist of three broad subregions: Micronesia, Melanesia and Polynesia. The islands here include the U.S. state of Hawaii, New Zealand, numerous independent countries, as well as territories belonging to the United States, New Zealand, France, the United Kingdom and Chile. While Melanesia and Polynesia both have some relatively substantial landmasses, Micronesia consists entirely of tiny islands. But regardless of the subregion, the small polities in the Pacific all face near-impossible struggles to maintain economic viability and protect their interests on the world stage.

In antiquity and during much of the colonial period, these islands were largely self-sufficient within a broader web of loose political, cultural and trade networks. In the contemporary world, however, their distance from global centers of consumption, as well as major maritime shipping routes, means most have failed to foster self-sustaining economies, bring products to market, provide for their domestic energy needs or, in many instances, even maintain maritime or aviation connections among their disparate islands. These islands are, in essence, “sea-locked” — meaning outside assistance from larger powers is critical.

If these countries and territories’ main challenge is that they are “small island nations,” their main asset is that they are “large ocean nations.” The Pacific is akin to a vast desert in which these islands, atolls and reefs offer potential frontier oases for the ocean’s great powers. Taken together, the islands possess a total 19.9 million square kilometers (7.7 million square miles) in combined exclusive economic zones (EEZs) — twice the size of all U.S. land territory. Kiribati might have a population only just topping 110,000, but its EEZ is the 12th largest in the world. Its neighbors — in regional terms, at least — like the Federated States of Micronesia, Papua New Guinea and the Marshall Islands also have the 14th, 16th, and 19th largest EEZs, respectively. This is their primary asset, which they can use to attract resources and attention from great powers that seek to ensure access (or deny that of others) to meet their strategic goals. As a result, most of the smaller Pacific islands have an economy based on four pillars: migration, remittances, aid and bureaucracy — all of which to some degree require access to or patronage from larger powers.

For the United States, the Pacific “stepping stones” have long presented an opportunity, as well as a threat.

Where America Meets Asia

For the United States, the Pacific “stepping stones” have long presented an opportunity, as well as a threat. The islands provide a space to project U.S. influence but also one that an enemy can use to menace U.S. shores. This understanding has underpinned U.S. strategy here since the 19th century: establish outposts and influence to gain strategic depth, while denying rivals the same.

The Pacific islands entered U.S. strategic thinking as the United States expanded westward, slowly transforming the formerly Atlantic-oriented power into one that straddled both oceans. During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the United States asserted its presence as one of many great powers in the stepping stones in the broader Pacific, gaining the Aleutians (1867), Midway (1867), Hawaii (1892) and Samoa (1904), as well as the Spanish holdings of Wake Island, Guam and the Philippines in 1898. Many of these islands were part of the broader great power struggle to secure coaling stations, lay submarine cables and ensure steady access to lucrative trade with China.

As Japan rose to become a power in its own right, Washington began to view its island possessions as forward positions that would ensure that any battle with Japan would remain in the western Pacific, far away from the U.S. West Coast. In 1914, however, Japan seized control of German possessions in Micronesia; after World War I, the League of Nations granted official mandate control over the area. During World War II, Imperial Japan seized most U.S. Pacific holdings and launched a devastating strike on U.S. naval forces in Hawaii, prompting the United States to respond with an island-hopping campaign that encompassed Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesia and, finally, Japan. The grueling fight cemented the United States’ resolve to use the ocean’s islands as “unsinkable aircraft carriers” to contain ambitious Pacific powers, permanently chasten Japan and, later, counterbalance the Soviets and the Chinese.

After World War II, U.S. strategic thinking centered on the two island chains. To this end, Washington assumed control of critical parts of the second island chain, namely, the Japanese League of Nations mandate islands in the Micronesian subregion, which later became the U.S.-administered U.N. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands, encompassing the Federated States of Micronesia, Marshall Islands, Palau and the Marianas. In this second island chain, the Micronesian subregion was the keystone that linked all the others.

Fraying Trust

Since that time, however, the U.S. relationship with the islands in Micronesia has become more complicated. By 1994, the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia and Palau had become independent countries in free association with the United States. Under these Compacts of Free Association, the United States provides high levels of aid and defense in exchange for rights to maintain armed forces bases and exclude third-party military access to the islands.

Today, the three countries’ relationship with the United States is contingent on mutual benefit. Between 1986 and 2003, the Federated States of Micronesia received $1.5 billion in U.S. aid, while the Marshall Islands obtained $1 billion, allowing the respective capitals, Palikir and Majuro, to employ civil servants and bankroll development projects. U.S. government agencies also provide services that the local governments cannot offer, such as aviation tracking, disaster and weather monitoring, postal services and other necessities. And because of the agreements between Pacific states and Washington, many Micronesians and Marshallese have taken jobs in the United States, sending back remittances that are critical for the local economies.

For the United States, the compact arrangements provide strategic benefits by denying rival powers footholds that could threaten U.S. interests. Under the compact, the United States can block access to a third country’s military and veto local decisions that conflict with U.S. defense rights and duties. After all, the states of Yap and Chuuk in the Federated States of Micronesia are both within striking distance of Guam, a U.S. territory and key bridgehead in the western Pacific that would play a strategic role in any Pacific conflict. If U.S. enemies managed to station aircraft on Kosrae, also in the Federated States of Micronesia, they would be within striking range of Hawaii and Australia. In the Marshall Islands in particular, the United States maintains access to Kwajalein Atoll for missile testing and tracking of foreign missile and space launches. In August 2017, Washington also announced that it would install radar systems in Palau to monitor North Korean missile launches.

In the event of a broader Pacific conflict, U.S. control of the Micronesian subregion would be vital to maintaining sea lines of communication. And if chokepoints in the Southeast Asian archipelago became blocked, eastward trade from the Middle East and South Asia to the Americas could be routed south of Australia before potentially passing the Micronesian subregion. As it is, maritime traffic between U.S. allies Australia and Japan already passes through the Federated States of Micronesia near Chuuk.

The Downsides of the Compact

Over the years, however, the compact has faced domestic U.S. scrutiny as to whether the aid is fostering local dependence and creating a bloated, inefficient bureaucracy; some in Washington have also questioned whether the compact actually provides the United States with any strategic value. In the Micronesian countries as well, some politicians have called for an end to the arrangement so as to exercise greater sovereignty and cultivate links with non-U.S. patrons. In 2016, the Federated States of Micronesia’s legislature passed a resolution calling for its president to restrict EEZ fishing access and instead license it out to a single foreign country, highlighting China as an option. In 2018, some politicians in Palikir pushed for their country to terminate the compact before 2023, but other lawmakers rejected the demand.

Unless the member state unilaterally terminates the compact, U.S. defense relations will remain, and even in that case, separate bilateral treaties would stipulate a continued defense relationship. But after the compact for the Federated States of Micronesia and Marshall Islands ends in 2023 (for a variety of reasons, Palau’s compact will not end until 2044), U.S. assistance will be replaced by a jointly administered trust fund meant to wean the islands off of aid. In 2024, meanwhile, Palikir and Majuro, the capitals of the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands, respectively, will lose access to the other benefits provided by the U.S. government to compensate for the lack of key domestic services.

Projections for the trust fund, however, indicate that the countries will not earn any money in many of the years and only small returns in others. For Palikir, this means losing out on funding that accounts for 33 percent of government expenditures and for Majuro, funds that account for 25 percent. As a result, the Federated State of Micronesia will face revenue shortfalls of an estimated $41.3 million per year in 2024, $60 million in 2030 and around $90 million in 2040. And in spite of positive GDP growth figures of over 3 percent for both countries in 2017, growth has been uneven for decades — even dipping below zero in some years.

Budget shortfalls could leave the countries looking for other patrons — like China — besides the United States to attract tourists, access markets to import and export agricultural products and fund critical infrastructure, particularly ports, energy and telecommunications. And while the United States will retain defense rights on the islands after 2024, the Federated States of Micronesia and the Marshall Islands will have a degree of latitude in terms of interpreting the provisions — something that could slowly erode one of the United States’ westernmost defensive lines if, for instance, China begins to encroach on the area. In all of this, U.S. allies like Australia, Japan and South Korea will be critical in helping counterbalance possible Chinese influence, as all three have a strategic interest in maintaining leverage in the island chains.

China on the Horizon

In proportion to its rapid rise to regional prominence — and global importance — China has increased its influence in the broader Pacific. At present, Beijing’s primary strategic focus is on the first island chain. Its buildups in the South China Sea and overtures to the Philippines and other U.S. allies are part of a broader strategy to ease this strategic threat. The second island chain, however, is also on China’s strategic horizon, since it presents a long-term roadblock to Beijing’s global maritime ambitions. Given the small size of these island countries, China has more than a few tools at hand to make substantial inroads — and at very little cost to boot.

China signaled its interest most clearly in 2006 when then-Premier Wen Jiabao became the first top Chinese leader to attend the China-Pacific Islands Countries Economic Development and Cooperation Conference in Fiji. In 2013, meanwhile, China included Pacific islands as part of the Maritime Silk Road component of its newly announced Belt and Road Initiative. And, one year later, Chinese President Xi Jinping attended the Pacific Island Forum, upgrading Chinese relations with regional diplomatic allies to the level of strategic partnership.

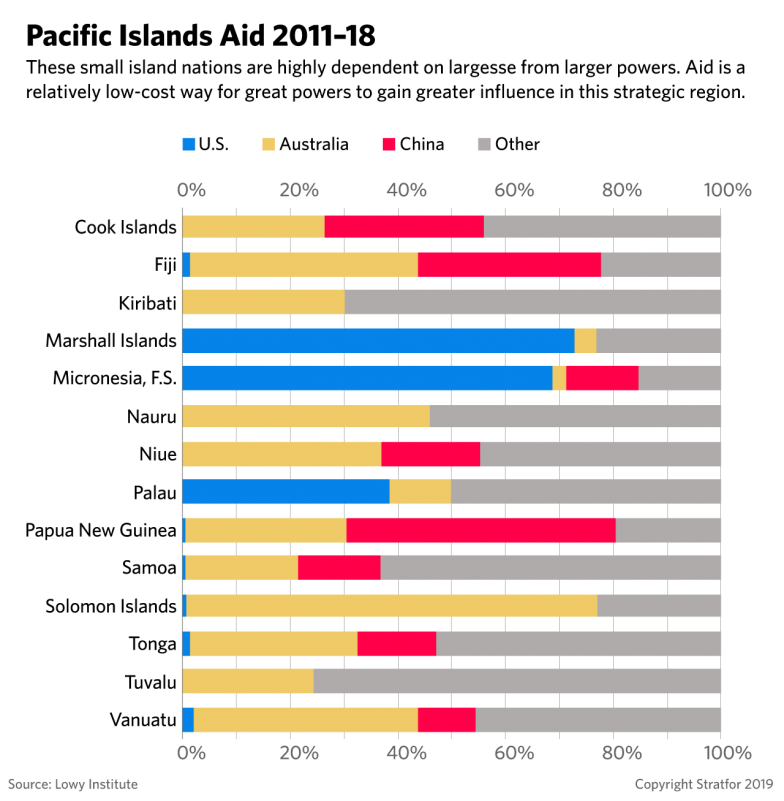

At present, China’s overtures center largely on eight countries and territories: the Cook Islands, Fiji, Niue, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Tonga, Vanuatu and the Federated States of Micronesia. China’s reach in the Pacific has grown gradually since the 1990s. The countries of Melanesia are of particular interest to China given the many mineral resources there. Between 2007 and 2017, Chinese trade with the Pacific islands as a whole rose fourfold to $8.2 billion, finishing just ahead of South Korea; U.S. trade, by contrast, totaled just $1.6 billion. One of Beijing’s top export recipients is a compact state, the Marshall Islands, which conducted more than $3 billion in trade with China in 2017, largely consisting of ships. And in the Federated States of Micronesia, China has already poured hundreds of millions of dollars into the country over the past two decades and contributed funds to fill the coffers of the post-compact trust fund.

Given the small size of these island countries, China has more than a few tools at hand to make substantial inroads — and at very little cost to boot.

Elsewhere, the massive growth of China’s global fishing fleet and the country’s large and growing demand for maritime protein has resulted in a massive uptick in Chinese fishing vessels plying the Pacific. Chinese regional foreign direct investment also rose 173 percent to $2.8 billion from 2014 to 2017, while development assistance to the region rivaled that of the United States, hitting $1.7 billion from 2006 to 2014. Tourism is the top services export for many Pacific island countries and from 2009 to 2014, Chinese tourist flows rose nearly 30 percent per year, with nearly 80 percent of Chinese visitors heading to either Palau or Fiji. China, too, is making inroads into territories that remain formally part of the United States, such as the Northern Mariana Islands, where Chinese companies are building casino resorts on Saipan and Tinian islands, in proximity to U.S. military operations.

Even as compact agreements end, the United States will continue to be a key actor in countries like the Federated States of Micronesia, the Marshall Islands and Palau. As times change, however, these island countries will draw more attention from the giant that lies to their west, especially as Beijing’s assistance comes with fewer strings attached, in contrast to Washington’s demands that local states engage in good governance and improve efficiency. For the moment, China’s outreach to many Pacific islands remains in its infancy, but the low cost — and long-term rewards — of such overtures mean the region will be the focus of Beijing’s interests for decades to come.

Stratfor

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook