On March 15, 1883, the day after Karl Marx died, Friedrich Engels wrote to the German-American Socialist leader Friedrich Sorge to give him an account of the illnesses that led up to Marx’s death. He went on to tell Sorge just how Marx breathed his last, and how Engels himself was trying to come to terms with the loss of his dearest friend and comrade of forty years:

All events that take place by natural necessity bring their own consolation with them, however dreadful they may be. Medical skill may have been able to give him a few more years of vegetable existence, the life of a helpless being, dying – to the triumph of the doctors’ art – not suddenly, but inch by inch. But our Marx could never have borne that. To have lived on with all his unfinished works before him, tantalised by a desire to finish them and yet unable to do so, would have been a thousand times more bitter than the gentle death which overtook him. ‘Death is not a misfortune for him who dies, but for him who survives’, he used to say, quoting Epicurus. And to see that mighty genius lingering on as a physical wreck to the greater glory of medicine and to the scorn of the philistines whom in the prime of his strength he had so often put to rout – no, it is better, a thousand times better, as it is – a thousand times better that we shall in two days’ time carry him to the grave where his wife lies at rest.

A little later in the same letter, Engels adds, quite simply: “…mankind is shorter by a head, and the greatest head of our time at that”.

Few men have paid a more moving tribute to a friend. Two days later, on Saturday, the March 17, as Marx was being lowered into the same grave as his wife’s, Engels spoke in the same vein:

On the 14th of March, at a quarter to three in the afternoon, the greatest living thinker ceased to think. He had been left alone for scarcely two minutes, and when we came back we found him in his armchair, peacefully gone to sleep – but for ever.

Incredible as it may sound, there were no more than 11 or 12 mourners as Karl Marx, the colossus who was to tower over the 20th century as perhaps no other individual did, was laid to rest that early spring day in Highgate Cemetery at Camden, north London. This, despite the fact that by then Marx had lived in London for close to 34 years, or more than half his life – an exile disowned and disenfranchised by the country of his birth and declared persona non grata by several others where he had sought to live and work as a fugitive from his native Germany. He had established no place of significance in the politics and intellectual life of Britain.

Indeed, at his death Marx did not have a lot to show for his life’s work: his major political effort since the failure of the 1848 revolution, the First International, had foundered by 1873. He had written some brilliant pamphlets and polemical treatises, besides of course the first part of Das Capital, which together were to form the primary intellectual equipment of the initiators of some the most important revolutionary movements in history. His sundry theoretical explorations were eventually to leave their permanent imprint on sociology, historiography, anthropology, aesthetics and even the cognitive sciences in a manner without parallel.

But all that was as yet in the future, and for now, but for a not insignificant group of followers in the continental socialist movements, Karl Heinrich Marx was a little-known man. His influence on British socialism had indeed waned in the wake of the Paris Commune of 1871, when the implacable hostility of the British propertied classes to all ideas of social change had sent even English trade union leaderships scurrying for cover, away from all variants of radical ideology.

An unremarkable grave

So, Engels led a tiny group of family and admirers to the cemetery comprising, besides Marx’s two surviving daughters Laura and Eleanor, the French socialist leaders Paul Lafargue (Laura’s husband) and Charles Longuet (husband to Marx’s eldest daughter Jenny), Prof Roy Lankaster and Prof Schorlemmer (both revered men of science and members of the Royal Society), the German Socialist leader Wilhelm Liebknecht, G. Lochner (a veteran of the Communist League), another battle-scarred German socialist F. Lessner (sentenced in the 1852 Cologne Communists’ Trial to five years’ hard labour), and writer-editor Gottlieb Lemke. It is possible that Helene Demuth, long the Marx family’s devoted housekeeper and friend, who would be buried alongside the family a few years later, was also in attendance. Highgate Cemetery traditionally had a section set apart for agnostics and atheists, making it the obvious choice for the Marx family to bury their dead in.

The proceedings were brief. Lemke laid two wreaths with red ribbons upon the coffin, one each in the name of the journal of the German Socialists and the London Communist Workers’ Educational Society. Then Engels made the funeral oration in English. He spoke of how his friend had been “the best-hated and most calumniated man of his time”, but also “beloved, revered and mourned by millions of revolutionary fellow-workers – from the mines of Siberia to California”.

Wilhelm Liebknecht spoke on behalf of German workers, in German, and Longuet followed with three messages from Russian, French and Spanish socialists, all in French. Once it was all over, the cortege wended its way back to Marx’s Maitland Park home. A few days later, Karl’s name was etched into the simple stone tablet that stood over his wife’s grave. Just five days later, some of these same mourners would be back again in Highgate, this time to bury five-year-old Harry Longuet, the youngest child of Marx’s eldest daughter Jenny who had pre-deceased her father.

The grave was as unremarkable as the burial. Hidden away in a little-known part of the cemetery, it was known to have baffled visitors who wanted to pay their respects at the grave but found it hard to locate. At a British Socialists’ conference in 1923, a leader rued how he had “some difficulty in finding it” and, once he managed to reach it, how “an old withered wreath, which appeared to have been lying there for years, and an old flower-pot with a scarlet geranium in bloom, were all that commemorated that great leader”.

It was on a sun-drenched late summer’s day in 2012 that I made my way to Highgate. It was no longer difficult to find the grave. Far from it, indeed. The East Highgate Cemetery, home to the Marx tomb since 1956, had a large number of visitors, mostly elderly men and women with chirpy grandchildren in tow. The few younger visitors appeared to have all come from China and Japan. There were no geraniums to greet me, but beds of white gladiolas splendidly set off bushes of red carnation and yellow iris, and rows of blue lilacs ran along the sides of the graves.

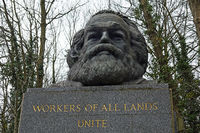

Presiding over it all, on a granite plinth some ten or 12 feet high, sat a bronze bust of the great man himself, looking on as all the commotion gathered around him, his bushy eye-brows and formidable beard twirling into a wry smile. The ringing words with which the Communist Manifesto ends, “Workers of All Lands, Unite” were emblazoned in gold letters on the plinth, as was another equally famous quote, on the lower end of the pedestal, this time from the Theses on Feuerbach: “The Philosophers have only Interpreted the World in various ways. The point however is to change it”.

While the general air could not have been described as charged by revolutionary fervour, two middle-aged couples sat in solemn contemplation on one side, apparently oblivious to the animated goings-on around them. The August breeze rustled in the silver birch and aspen trees strung around the graves.

Marx’s new ‘home’ dates back to 1956, when the Communist Party of Great Britain decided that it would no longer do to leave the Master’s grave hidden away in an obscure corner. So, a more prominent plot was procured in the eastern part of the great cemetery, apparently at significant cost, and the Marx graves were relocated in a ceremony where Harry Pollitt, general secretary of the CPGB, unveiled the new monument on March 14, 1956, the 73d anniversary of Marx’s death.

The socialist sculptor Lawrence Bradshaw had been charged with designing the new monument, and he created the bust that now crowns the memorial. It is the massive head that dominates the bust, though. One is reminded of Engels returning again and again to his theme of the loss, in Marx’s passing, of one of mankind’s great ‘heads’.

There is a certain irony about the timing of the new tomb. Through the 1940s, as communism gained ground internationally up to a point where one-third of humanity lived under regimes that professed allegiance to Karl Marx, his grave lay in a mostly non-descript corner. On the other hand, 1956 was the year when the communist monolith that claimed to have modelled itself on Marx’s teachings, showed its first cracks. The USSR’s invasion of Hungary and the suppression of a genuine uprising in Budapest were unmistakable pointers to the fault-lines within a system that had laid the most serious claim yet to Marx’s legacy.

Just a few months after Pollitt did the honours at Marx’s grave, Soviet tanks rolled into Hungary’s capital city, sparking outrage not only in liberal democracies in the west but even within the CPGB itself. The Communist Historians’ Group, led by E.P. Thompson and Eric Hobsbawm wrote an open letter to the party leadership, decrying its silence over the invasion. At any event, after 1956 the world of Marxian socialism was never quite the same again.

Only a couple of months after I went and paid my respects at Marx’s grave, Hobsbawm passed away, to be buried, like some other Marxists, British and non-British, close to the man they probably admired most. But while it is not surprising to find men such as Yusuf Dadoo, the great South African communist and anti-apartheid activist, laid at rest in their teacher’s shadow, you cannot miss the irony of the grave of Herbert Spencer, the well-known liberal theorist and Marx’s ideological antithesis, lying almost directly opposite Marx’s.

There is more news yet. With 2018 marking Marx’s birth bi-centenary, a fresh sprucing-up of the monument at Highgate has been planned for this year. The plan, supported by Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn among others, includes installing slabs of black granite “with a flamed finish”. As the British Labour Party tries to reinvent itself, a new-look Marx monument now awaits visitors.

Anjan Basu

Click here to subscribe to our weekly newsletters in English and or French. You will receive one email every Monday containing links to all articles published in the last 7 days.

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook