It is true that globalisation has created benefits for consumers, businesses and suppliers. It is propelled, however, by global supply chains, or the dominant practice of sourcing goods and services from developing countries where wages are low, laws are lax and governance of supply chains is ineffective. Today’s unprecedented level of inequality, prolonged wars, and increasing threat of climate change brought about by the insatiable drive for profit also produces and relies on a global human supply chain.

Jennifer Gordon’s “Regulating the Human Supply Chain” analyses the relationship between US laws and employers’ recruitment of would-be migrants from other countries. This practice, which is becoming increasingly global, creates a transnational network of labour intermediaries—the “human supply chain”—whose operation, as Gordon argues, undermines the rule of law in the workplace, benefitting US companies by reducing labor costs while creating distributional harms for US workers, and placing temporary migrant workers in situations of severe subordination. It identifies the human supply chain as a key structure of the global economy, which has a very close relationship to the more familiar product supply chains through which many transnational companies manufacture products abroad.

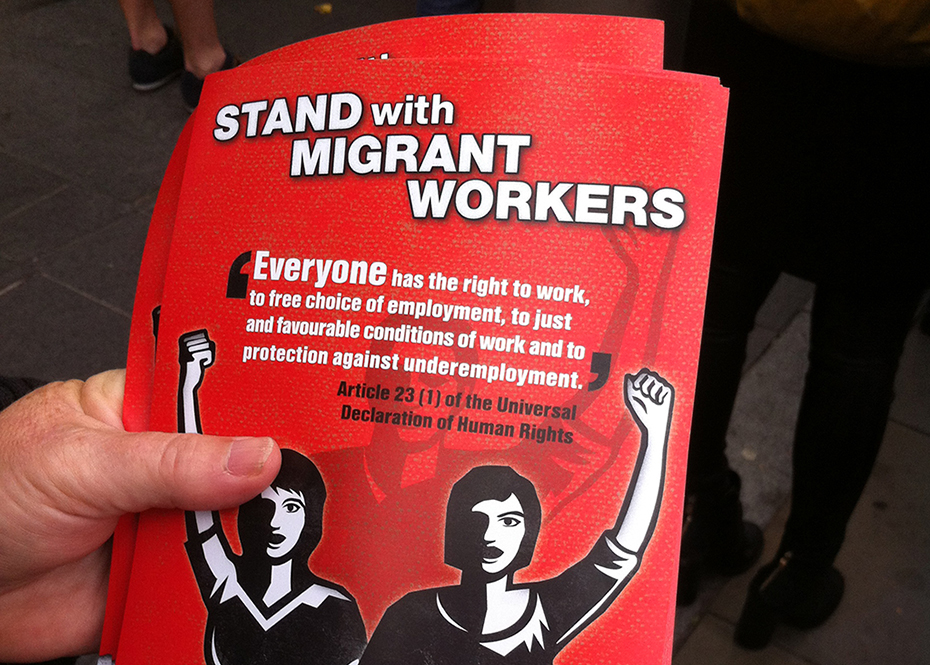

Hostile border laws and environments in host countries lead to conditions in which migrant workers are treated as interchangeable, disposable bodies with no rights, and as deportable with no future. Rather than becoming beneficiaries of globalisation, workers are instead pitted against each other. This reality is not accidental, but rather deliberate and is at the heart of the global economic order.

Global supply chains

The supply chains that enables multinational companies to accumulate profits now control some 80% of world trade and 60% of global production. Furthermore, nearly half of the world’s largest companies directly employ just 6% of the workers in their supply chain. The remaining 94% are part of the hidden workforce of global production. This marginalises workers and often contributes to a denial of their rights.

Supply chain workers in all sectors of production: textiles, retail, fisheries, electronics, construction, tourism and hospitality, transport and agriculture, etc, are integral to the global economy. However, workers, especially migrant workers, often face poverty and exploitative and discriminatory wages, dangerous and unsafe working conditions, and very limited rights on the job.

The term “migrant for employment” is defined in Article 11, paragraph 1, of Convention No. 97 of the International Labour Organisation as “a person who migrates from one country to another with a view to being employed otherwise than on his [sic] own account and includes any person regularly admitted as a migrant for employment”. In 2017, the ILO found that migrant workers accounted for 164 million of the world’s approximately 258 million international migrants.

The push by suppliers and job agencies to squeeze wages often results in jobs that are insecure and informal, involving dangerous workplaces, forced overtime and working conditions that are, in certain instances, even akin to slavery. Most often because they are foreign and unaware or directly denied their rights legally in the host countries, workers are denied the right to freedom of association.

Migrant workers in the UK

There are approximately five million non-British nationals working in the UK, accounting for 17% of the workforce. In hospitality and tourism, 24% of the 1.75 million workforce is made up of non-British nationals, with the majority coming from outside the EU. In comparison, there is 14% in retail, 15% in travel, and 21% in care.

It is important to understand that the presence of migrants in the UK is a product of both this country’s history and its historical role in shaping the present global order. The massive wave of global migration, estimated by the UN to be close to 260 million migrants with 68.5 million displaced people and 25.4 million refugees in June 2018, shows the desperation of people who are being pushed by increasing inequalities produced by the continuing expansion of global capital and those who are fleeing war or persecution.

Migration is a phenomenon linked with privatisation, free trade, growth-oriented and extractivist economic policies that governments worldwide have pursued since the 1980s. The UK, as one of the most influential countries in multilateral global policymaking and governance institutions, is one of the architects of the current economic, trade, and financial regimes which have produced these policies.

Many studies show that migrant labour experiences higher rates of exploitation and that trade unions in sectors with high levels of migrant labour find it difficult to maintain high levels of unionization and comprehensive collective bargaining which in turn would raise wages and increase protection.

The Immigration Bill will contribute to further exploitation of migrant workers and divide all workers

This brings us to the UK government’s latest Immigration Bill, which it is rushing to pass before Brexit, and the associated white paper which sets out its future plans. As a “transitional measure”, the white paper talks about allowing people from “low-risk countries” in Europe and further afield to come to the UK, without a job offer, and seek work for up to a year. This scheme will fill vacancies in sectors such as construction, hospitality and social care which are heavily dependent on foreign labour and which ministers fear could struggle to adapt when free movement ends. This dilemma was not created by migration, but rather constructed by division of labour and cost-cutting in these sectors.

Workers entering the UK under this category must pay a fee and not get access to public funds. They will not be able to switch to any other migration scheme nor switch employers. There will be a “cooling off period” after a year, which means people will be expected to leave the country and not apply again for 12 months. This immigration system is designed to ensure a flow of unskilled labour, in which workers are unable to organise and have few political rights.

This will result in further exploitation of local and migrant workers in the supply chains as businesses will be allowed to enjoy the continued benefit of outsourcing various functions and parts of work to various workers without bearing the true cost of production and service provision. This ensures that products and services will be produced without giving full rights and benefits especially to workers. There will be no incentive to train or promote them since they will leave after a year. This will also ensure that the difficulty of organising worker unions continues, and the further weakening of unionism in the country, reducing the power of all workers.

Dorothy Grace Guerrero

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières

Twitter

Twitter Facebook

Facebook